Working, Poor: South London women share their experiences of in-work poverty

Our current piece of research is about in-work poverty, particularly women’s and mothers’ experiences of this.

Researchers and media professionals we have encountered have talked to us of their struggle to really access the granular experience, the detailed stories of women experiencing ‘in-work poverty’. They were able to access and analyse quantitative data and policy documents. But the stories were missing. The women in our group saw the importance of what they, and participatory research, carried out by people close to those situations, could bring to our understanding of the experience of in-work poverty.

“We know those stories. Some of us are those stories.”

Here we present some of the stories we found out about in the course of our research.

Listen to our podcasts here

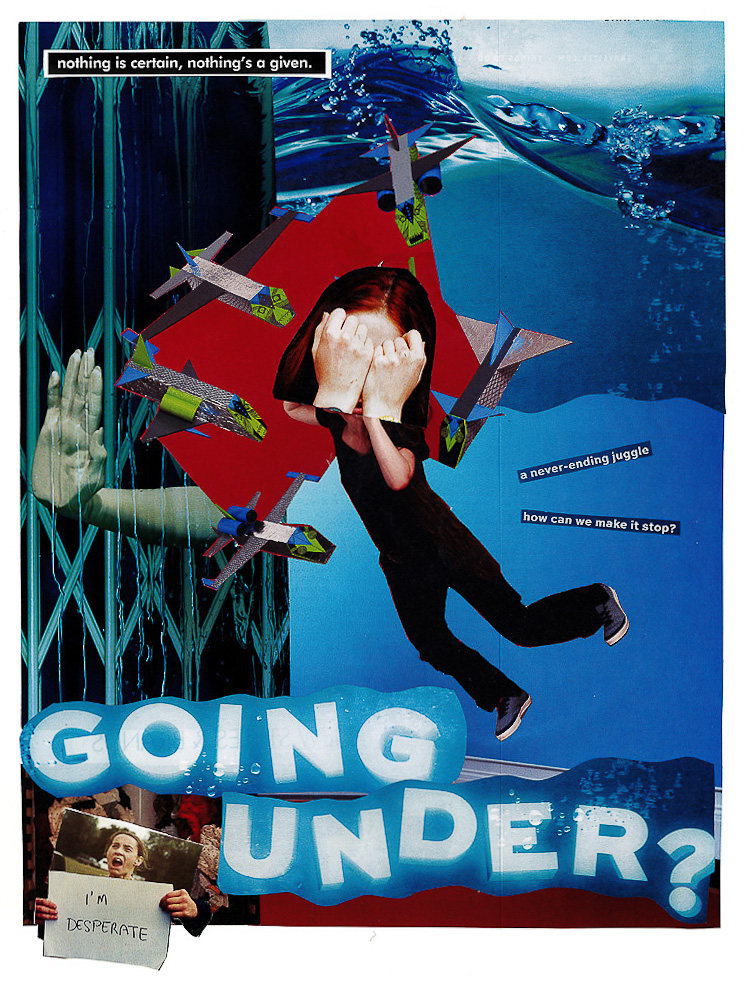

There are some positive stories. There are also stories of exhaustion, frustration, and instability; stories of bewilderment at how after working so hard they get so little. There are stories of blame and recrimination. There are also stories of hope and stories of resistance.

Extensive research shows in-work poverty, and austerity in general, disproportionately affects women. However, there is more to poverty than money. Lack of choice, feeling stuck in a rut, not being able to plan for the future and a reduced sense of self-worth are all part of the emotional toll poverty can take. Cuts to public services hit women the hardest, as women almost always fill the gaps in care and community services, doing the jobs themselves for free.

Our story, as participants and peer researchers, is that we cannot completely avoid paying the social and emotional costs of in-work poverty. We can only shift around who pays for it – whether children or parents – and when.

The Impacts of In-Work Poverty

Poverty is the difference between living and merely existing. It is not a metric, it is fluid and shifting.

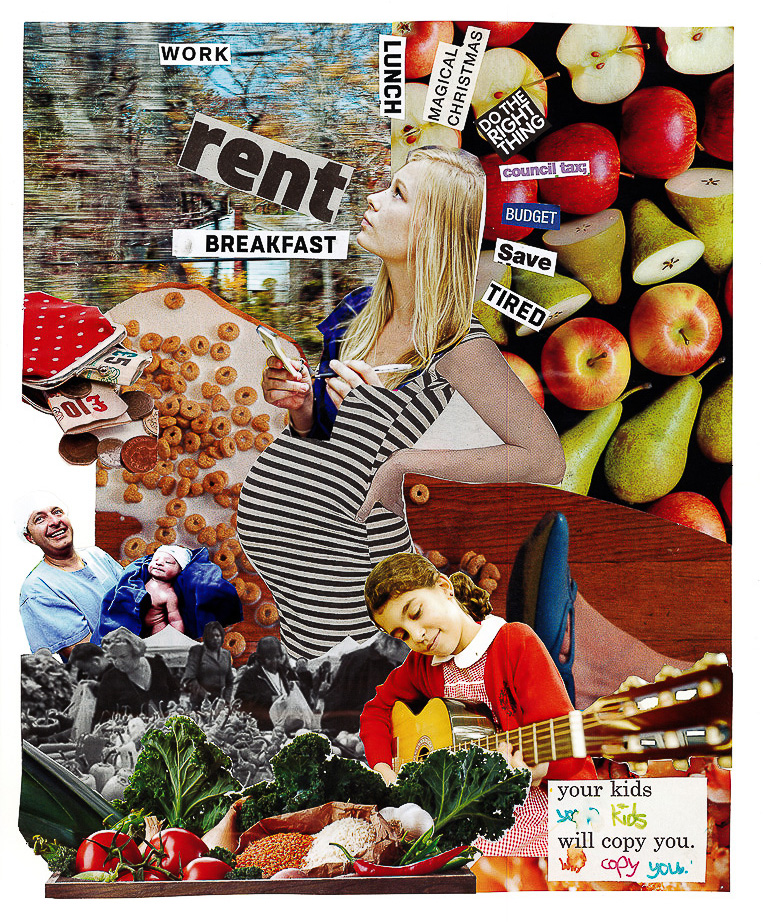

Some participants were shocked and confused by the lack of difference having a job made in their lives. Financially many felt no better off, or were actually worse off as they had new expenses associated with working, such as transport and childcare. To meet these costs participants sometimes went into debt, borrowed from family members or sought charity.

However, in-work poverty does not just affect a person’s household budget. It also affects their mental and emotional health, their relationships and their ability to plan for the future. Living in debt, juggling bills and time pressures are often linked to stress and anxiety, which both take a toll in the long term. Interviewees described being constantly preoccupied by financial concerns and not being able to meet their families’ needs.

One of the most beautiful things I did (at Skills Network) is the research. I am so proud of it. When I carried that book, I was just somebody… I went to people’s houses, interviewed the person, we have to come back to analyse the story. We had policy meetings with different people … (you learn) how to handle yourself.

Some of the women we spoke to felt they needed to put a brave face on for their families, but this left them feeling alone and without support for what they are facing. While some thought staying connected to their community was vital, others felt that experiencing in-work poverty made it hard to socialise or spend time out of the house. One interviewee said: “Only people that have money … have a social life.”

While some of the emotional and social costs identified by our participants would no doubt be familiar to people experiencing other kinds of poverty, there are some that are specific to low-income work. Disillusionment about work, the stress of insecure work arrangements, or the impact of working hours on children can all be difficult to manage.

Working Women; Working Mothers

“Most women … worry less about being able to break through the glass ceiling than they do about falling through a structurally unstable floor.” Kathi Weeks, The Problem With Work

While it is essential that women have equal opportunities to undertake formal paid work, it is important to recognise the additional pressures on women who perform the majority of unpaid care and domestic work. We are still at an immense disadvantage when it comes to trying to hold down work, be a parent and maintain a sense of individual identity at the same time.

It seems pregnancy itself can be the point at which women start the slide into cycles of poverty. This may be due to health problems, difficulties in continuing to work or an end to educational or career possibilities. Yet despite having caring responsibilities, there is a lot of pressure on women to re-enter the workforce as soon as possible after having children, even if it is to the detriment of their family. Working as much as possible to pay someone else to look after your children can seem illogical and counterproductive. Many of our interviewees experienced conflicting societal pressures, feeling they were failing as a mother, as a worker, or both.

“In Africa, we have less money there, we have less stuff to support ourselves. But on the other hand, we have the privilege of being a mother.” Research participant

Many women we interviewed were worried about passing stress onto their children. Mothers spoke of having to work through school holidays, struggling to keep up with necessities like food and of not being able to provide social outings for their children or even manage school trips. Some worried that not fulfilling themselves as a person, for example through feeling demeaned and exploited at work, would affect what their children thought they could achieve in their own lives. However, some mothers also expressed hope their children would end up more understanding and better able to handle adversity because of their difficult situations.

The women we spoke to were far from passive victims. They identified strategies for coping with the day-to-day difficulties they face. This includes focusing on prospects for a better future, especially providing their children with a better life. Their skills and determination demonstrate an inner ‘resilience’, a characteristic increasingly celebrated over the past decade. But this raises an important question: How far should we celebrate ‘coping strategies’ that result from bleak and unfair working conditions?

The women we spoke to were happy to work and wanted to avoid reliance on state support at all costs. But two demands were clear: (1) better financial and emotional support in order to stay in work, and (2) more autonomy to integrate work alongside caring responsibilities.

Challenging Prevailing Narratives

An important aim of this project was to examine and challenge the language government and media tend to use around work and welfare. This included looking at loaded terms like ‘choice’, ‘help’, ‘responsibility’ and ‘fairness’. Too often people are falsely separated into ‘strivers’ or ‘skivers’. The idea that you are either a hard-worker or a ‘benefit scrounge’ ignores the reality that many people have to balance paid work with unpaid responsibilities, such as childcare. Current rhetoric around ‘aspiration’ implies people just need to try harder, ignoring systemic constraints and structural inequalities. These types of narratives seek to impose simple identities on complex lives.

Policies designed to ‘help’ families may perversely lead to less family time and poorer family relationships. Policies that could be more ‘helpful’ to parents include shorter working days and flexible working hours. No matter how hard you work, neither families nor individuals can overcome entrenched privilege and structural inequalities. Historically, solidarity and collectivity have been needed to achieve these aims.

The women we interviewed often felt that if they made what the government would call ‘responsible’ choices, it was to the detriment of other aspects of their lives, such as building family relations or engaging with their community in meaningful ways. Many of the women we spoke to felt the only ‘choice’ they had was between bad options. Similarly, the notion of ‘flexibility’, which is often touted as increasing choice, is seen as benefiting employers more than workers, as is the case with zero-hour contracts. Unstable hours and poor work conditions can lead to hardship, stress and insecurity.

Current government rhetoric seems to assume individuals end up living in poverty simply by making poor life choices. We challenge this perspective and instead propose adopting a capabilities approach, developed by economist Amartya Sen. This means focusing on what individuals are actually able to be and do, rather than looking at opportunities that are theoretically available but difficult or impossible to realise.

A New Way Forward

In-work poverty can mean many different things. How we define poverty and work has far-reaching implications for policy and how we provide support to people. It would be a positive step forward to value different kinds of work more equally in terms of reward and status. Not everyone can ‘contribute’ equally and some people have more needs. It is important to acknowledge that we all rely on each other.

There should be a recognition that other activities beside formal paid work are important and valuable too, such as creativity, social interaction and enjoyment. These contribute to stronger communities, where people can find a sense of belonging and are less likely to feel isolated. We also believe that we need to accept and embrace the different capacities, skills and knowledge present in our society.

Perhaps it is time policy-makers replaced the idea of homo economicus, the self-interested rational man, with homo reciprocans. In this conception of humans, we are viewed as cooperative actors motivated by improving our environment. Fostering cooperation, reciprocity and sharing also bring us closer to realising equality.

‘Aspiration’ is a complex idea that encompasses more than your financial lot. It includes wanting to spend more time with your children, building communities and realising alternative worlds. Let us think more about collective aspirations and how we can balance our needs and desires with those of other people.

Through the peer research project I have become more observant to current issues through the media and more aware of how these issues are being represented. I feel encouraged to question and think more independently on the bull that is being fed to me.

To read the full report on in work poverty, click here

If you’d like to read the previous report, about experiences of the job centre from south London women, click here